A narrator is a person who recounts the event of a novel or a narrative poem. They are otherwise known as a storyteller, chronicler, reporter or annalist to name a few.

A narrator can be viewed as a bridge between a narrative and the reader. The narrator gives a commentary to a narrative and helps contextualize the actions made by characters in a novel or narrative poem. The narrator can be of first or third person. A first person narrator is very common in literature. It is a point of view of one character who speaks about themselves

There are different ways a first person narrator can be used;

Ø Interior monologue – This is also known as an inner voice. It is where the character tells the story from their direct point of view.

Ø Dramatic monologue – This is a long excerpt where a single character’s thoughts and feelings are revealed. It usually addresses a silent listener and not the actual reader.

Ø Peripheral narrator – This is where a first person narrator, who is not the main character, witnesses the main’s character’s story and conveys it to the reader.

A third person narrator has a limited point of view since they only know the thoughts and feelings of the main character. They are not a figure in the story but rather an observer who is outside the action being described. A third person narrator is often omniscient meaning they can tell what the characters are thinking and they describe all characters using pronouns such as ‘he’ and ‘she’.

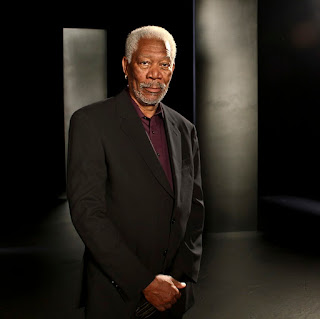

In film, voice-overs are a very popular, Morgan Freeman is perhaps the most famous example within film. His ability as a narrator in film has made him a world famous storyteller. He is regarded by many as a popular choice for the narrator’s voice.

A contrast exists between literature and film on how the voice of the narrator is portrayed. Within a film, the narrator’s voice is given to the viewer and they cannot influence it, whereas in literature the voice of the narrator can vary depending on the reader as well as the genre of text.

“The Count halted, putting down my bags, closed the door, and crossing the room, opened

another door, which led into a small octagonal room lit by a single lamp, and seemingly

without a window of any sort. Passing through this, he opened another door and motioned me

to enter. It was a welcome sight. For here was a great bedroom well lighted and warmed with

another log fire, also added to but lately, for the top logs were fresh, which sent a hollow roar

up the wide chimney. The Count himself left my luggage inside and withdrew, saying, before

he closed the door”

This is an extract from Dracula by Bram Stoker, it is a Gothic novel. When reading that extract the reader develops a voice for the narrator which fits the spooky mood of the setting, which would be different to them reading a romantic novel.

|

| :The act or process of telling a story or describing what happens :Words that are heard as part of a movie, television show etc..., and that describe what is being seen' |

However, narrators can only have an impact where a narration is present. In recent years, development within education and technology has caused narration to change. Through time narration has been seen in hieroglyphics, scriptures, novels and really any and all narratives. In all these, each narration has its own structure and despite the fact the different cultures around the world all have their own unique way of telling stories, there are some common traits in them all.

Vladimir Propp created a theory called ‘Propp’s narrative functions’ after noticing events in some narratives being repeated. This theory was made to clarify the 31 functions within those narratives. Of them all, there were seven common character types being the hero, villain, donor, helper, princess, false hero and the dispatcher. As we look over some of the narratives of the past and of today, we can still see these functions being used and therefore, the assumption of a narration having these functions within them is more than justified to say so.

Tzvetan Todorov simplified the idea of a narrative having five different stages to two, being his theory of Equilibrium and Disequilibrium. As narration is the “process of telling a story” Todorov’s theory is the stages of which this process is told. In most conventional narratives he argues the five stages to them are the equilibrium, the disruption, the recognition, the repair, and the new equilibrium. So, by Todorov’s standards if there was no conflict or disruption there would be no narration.

To summarise, narrators and narration intertwine in storytelling. In order for an author to effectively tell a story, they need to go through a process of telling the story according to Todrov's standards while including a narrator that tells the story from a specific point of view - it is entirely up to the writer and the effect they want to give to their reader.